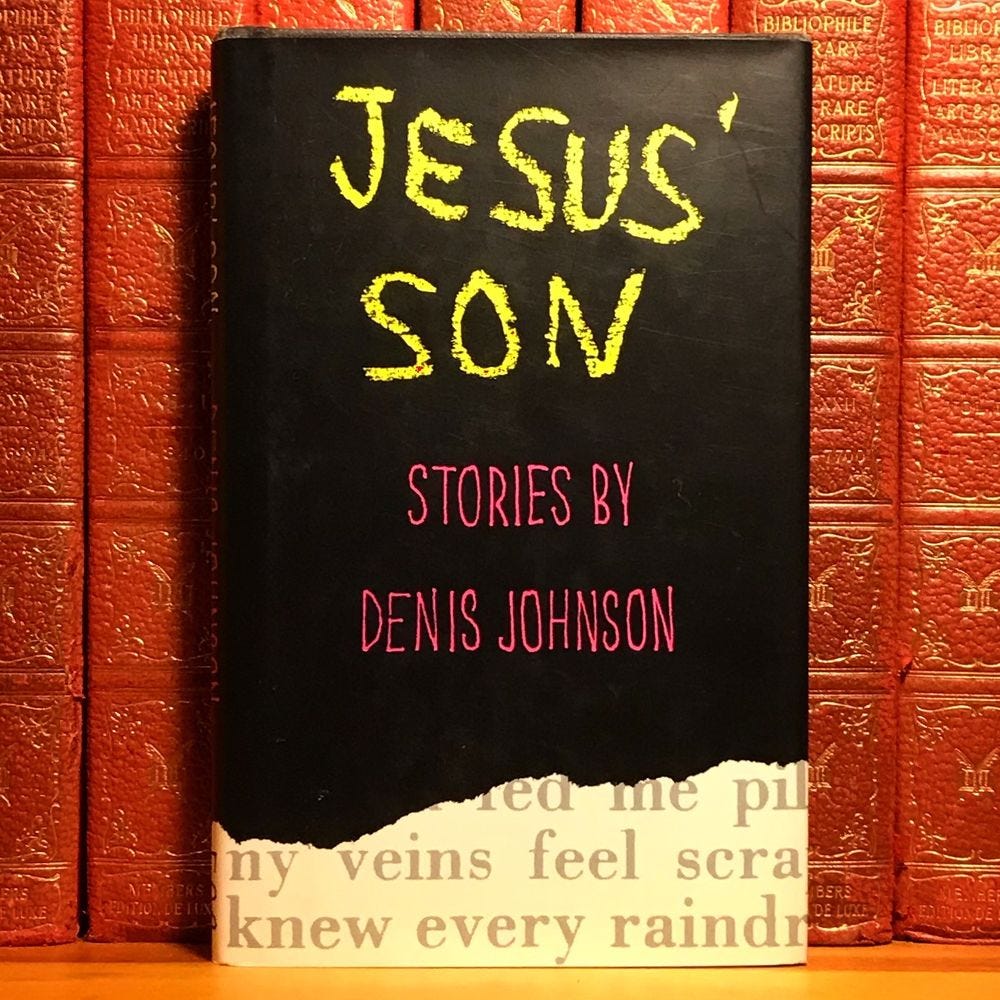

Please allow me to make a confession of sorts. Remember in grade school when a gentle and kind-hearted teacher helps to ignite your love of reading, and one of their stern but helpful reminders is to never judge a book by its cover? Well, unfortunately, for the longest time, that advice went unheeded. It wasn’t so much the cover I was judging, but the title. Right after college when I started taking literature more seriously, I heard about Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson through a few different essays and some of my more literary-minded friends. However, as embarrassing as it is to admit now, I avoided the book due in large part to the idea that I thought it was about some conspiracy involving the supposed offspring of Christ himself, done in the format of some even more petulant Dan Brown who thought he was using fiction to hold a mirror up to not just Christianity, but organized religion as a whole!

However, while completing classroom observations for my Master of Education degree, I was observing an English teacher who I both knew and very much trusted. This teacher interestingly enough had adorned his walls with the covers of all the books he had read in the last ten years. He said it was an interesting conversation starter, and sometimes incorporated it into activities with his students. Among the covers, I saw Jesus’ Son. Knowing this English teacher would not be among the reading public who would consume a Dan-Brown-esque religious conspiracy theory thriller, I asked him about it and eventually looked into it more and discovered it was actually a book about addiction. Shortly thereafter, I got it from the local library and shortly after that, finished it, reading it cover to cover in about 24 hours. To say I was floored would be an understatement.

Furthermore, it would not be an overstatement to say that Jesus’ Son challenged my previous beliefs in regards to what fiction is capable of, and truly showed me what an adept piece of fiction can do to contribute to the conversation about the human condition. Jesus’ Son, a novel which is actually a story cycle, or a collection of connected short stories, follows the same narrator as he recounts his days of boozing and shooting up heroin. However, the book quickly becomes more than just a means of trying to reveal shocking and deprecating party stories, instead choosing to focus on the bizarre social outcasts the narrator finds along his journey.

Jesus’ Son seems to succeed where so many other similar stories, novels, films, and TV shows have failed. And maybe that’s because, despite the deep dives into the dregs of humanity and the rock bottoms of society’s worst, the people contained in the stories are both human and startlingly three dimensional. Despite what some of them are willing to do for or because of their addictions, they never lose their humanity. This book isn’t so much about addiction itself, but more about the very people going through the cycle of addiction. The characters aren’t on display for us to gawk at, or to position in juxtaposition against our own lives (“wow, at least I’m not like that!), but are inhabitants of the stories to show the true humanity of suffering and the experience of perseverance, however unintentional. Addiction stories often suffer from either a romanticizing or fetishizing of consumption, or swing to the other side of the spectrum and seek to bludgeon the public consciousness into oblivion with the horrifying realities of addiction. Neither, in my opinion, can ultimately be successful, and suffers from one major flaw: it’s focusing too much on the act of using, and not on the people who are using. In focusing on the people, Jesus’ Son isn’t some form of addiction porn, but instead a story cycle of a human who is happy, sad, suffering, overcoming, living, experiencing, seeking, and striving.

Simply put, Jesus’ Son refrains from glorifying the cycle of addiction. Through most of the book, you get a sense the narrator is on an inevitable death march towards sobriety or his own demise, and like a ride he knows he’ll eventually have to get off of, is simply trying to seek one final moment of satisfaction before it’s over. At one point, the narrator enters a bar at happy hour around dusk, his favorite time because you “order one drink but are given two.” Realizing the futility of the situation, he remarks, “But nothing could be healed, the mirror was a knife dividing everything from itself, tears of false fellowship dripped on the bar. And what are you going to do to me now? With what, exactly, would you expect to frighten me?”

Despite the ever-present sense of hope throughout the book, the ending takes a bizarre turn when the narrator becomes sober (this isn’t ruining anything, because if you start this book without realizing he’s eventually going to sober up then I don’t know what to tell you) and replaces one vice with one decidedly much worse when he takes up voyeurism. This portion of the book is actually more shocking than anything he does while drinking or consuming drugs, and that’s saying something considering the orderly he works with in a hospital at one point pulls a hunting knife out of a guy’s eye when he was supposed to be prepping the patient for surgery. But the ending, and the odd foray into the protagonist’s deviancy, serves a purpose. While the book ends on a high note, it also ends alluding to the cyclical nature of people like the protagonist of Jesus’ Son, with fate or some other unseen force choosing the narrator as the rare lucky one that gets to overcome. The last lines of the book do more than suggest hope, they suggest victory, “All these weirdos, and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them. I had never known, never even imagined for a heartbeat, that there might be a place for people like us.” In closing, don’t read Jesus’ Son if you’re seeking anything heartwarming. Instead, come for the heroic prevailing of the common man.